Hard Vs. Soft Power

Foreign Policy Strategies in Contemporary International Relations

Event Review

‘Hard Vs. Soft Power’ was an international congress that explored the balance between hard and soft power in contemporary international relations and considered the future of the two approaches. It consisted of a four-day programme of lectures and panel discussions organised by the Institute for Cultural Diplomacy in cooperation with the Cambridge Union Society over the period Wednesday 23 June to Saturday 26 June.Since the end of the Cold War and the subsequent opening of the international environment, the pursuit of national interests abroad through hard power has come under intense scrutiny. The use of military force on foreign soil has in particular been criticised. The high profile examples of Iraq and Afghanistan provide fuel to arguments that such an approach cannot succeed in the complex tasks of nation building and fighting terrorism. Within this context, the concept of soft power and the use of cultural diplomacy have increasingly been put forward as alternative or complementary approaches.

‘Hard Vs. Soft Power’ began by exploring the origins, development, and contemporary understanding of the terms ‘hard power’, ‘soft power’, and ‘smart power’, and the extent to which they can be viewed as distinct concepts. Having explored the definitions of these terms, the focus of analysis then shifted to the balance of hard and soft power in the contemporary foreign policy strategies of nation states. Under particular consideration here were the changing nature of foreign policy priorities; the increasing importance of global public goods, and the challenges of pursuing objectives in an interdependent world. During the second part of the programme, case studies of soft power and cultural diplomacy were considered, and speakers were asked to reflect on the future of foreign policy strategies.

Each speaker’s contribution is summarised below. Finally, recurrent ideas or points on which there was notable consensus, controversy, or difference of interpretation are discussed at the end of the report.

Sam Jones

Head of Culture at Demos; DCMS FellowSamuel Jones is Head of Culture at British think-tank Demos and a Fellow at the Department for Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS). He has published a range of important pamphlets and reports on the topics of international and intercultural communication, Britain’s cultural diplomacy, new cultural industries, and the role of museums, libraries and archives in Britain’s social and cultural landscape. His speech focused on the growing importance of culture, broadly conceived, in international relations, and the responsibility of governments to promote cultural literacy.

The attractiveness of a country’s culture and how that culture is perceived abroad are among the key foundations of soft power. But in the United Kingdom, funding for culture in domestic and foreign policy is under threat. The new government is determined to cut government spending in response to a massive fiscal deficit. Funding for culture in domestic and foreign policy is not a high priority. Those priorities depend on the electorate, and in contrast with promises to ring-fence spending on the National Health Service or guarantee funding for the armed forces in Afghanistan, there is no widespread consensus on the value of government-funded culture.

Part of the problem is that culture is so difficult to define, which makes it all but impossible to produce a quantified, cost-benefit analysis of cultural spending. Culture is much more than state-funded, brick-and-mortar institutions such as museums, opera houses and libraries. Culture encompasses cuisine, television programmes and fashion, among so many others.

By its very nature, culture is never permanent but constantly evolving. The case of international English is illustrative: non-native speakers shape the English language as they use it, creating something like regional dialects. This national export has become an international cultural phenomenon, and the spread of new media has brought an unprecedented number of people into the cultural sphere. But in this new age of empowerment, there are also issues around equality of access.

Culture is an international network of power that governments are almost powerless to limit, but whose repercussions they are forced to manage. For example, speaking at a press conference while on an official visit to India, Prime Minister Gordon Brown was forced to answer questions about racist comments by a UK reality television star directed at an Indian colleague. Similarly, the film 300, which seemed to depict Persian culture in a negative light, became a diplomatic issue between Iran and the United States.

Governments have a responsibility to promote the cultural literacy of their citizens, just as they support their health and security. The informal practice of dividing school subjects into ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ subjects is ill-advised.

Simon Anholt

British Government Advisor, ‘Nation Brands Index’ FounderSimon Anholt is a British government advisor specialising in the field of ‘nation branding’, a term he publicly coined in 1998. He is a member of the British government's Public Diplomacy Board and advises a number of other governments on their branding strategies, several of them developing countries in collaboration with the United Nations. His speech emphasised the difference between marketing a country and using smart policy to manage a country’s international reputation.

There is an important difference between a nation’s ‘brand’ and the exercise of ‘branding’ a nation. The former is an observation of the prestige, attractiveness, or value attached to a nation by people in other countries. The latter is a questionable attempt to use the tools of marketing to manipulate those perceptions. For example, some Sub-Saharan countries use advertisements on international television channels to attract tourism and investment. Given the preponderance of negative images of Africa in the Western media, such efforts are at best comically ineffectual and at worst disastrously counterproductive.

Paradoxically, Africa’s grim reputation in the West is largely the work of the most well-meaning aid organisations. In order to secure donations, they make it their business to convince potential Western donors that conditions in some areas of Africa are catastrophic, and because little is heard of the rest of the continent, this negative image is associated with all of Africa. But countries’ reputations can also be ruined by their own political leaders. According to Anholt’s research, the majority of the world’s citizens believe Canada has a more valuable cultural heritage than Iran, a civilisation that stretches back thousands of years. Presidents Bush and Ahmadinejad must share some of the blame for this.

Anholt’s advice is simple: if a country wishes to be viewed in a positive light, it must act accordingly. Reputations are based on concrete acts, and, as a rule, countries get the reputations they deserve. We may choose not to spend our holidays in a certain country, for example, in protest against its government’s record on human rights. But Anholt’s surveys also show that people actually think very little about their own country, let alone others. This means that if a country wishes to improve its image, it must do more than improve its domestic policies. It must also play the role of global citizen and contribute to the ‘international commons’.

South Korea is a case in point. That country’s transformation from provincial backwater to economic powerhouse within the space of a single generation has dramatically changed the lives of South Koreans. Accordingly, surveys show that South Koreans rate their own country quite highly. But this achievement has not translated into higher esteem by other nationalities. When advising South Korea’s government, Anholt suggested that South Korea behave more like a conscientious global citizen. The government responded by quadrupling South Korea’s development aid budget. In the same way that Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) has effected a quiet revolution in business practice, something we might call ‘Government Social Responsibility’ is changing the rules of international relations.

In some respects, international relations today might be compared to a ‘gigantic global supermarket of national brands’, to use a phrase coined by one of Anholt’s detractors. At first blush, this may sound unappealing, but it is actually much fairer than the previous system. In the past, international influence was based on military strength alone. Might, by definition, was right. Today niche players can prosper, and morality is no longer irrelevant.

Sharath Srinavasan

Director of the Centre of Governance and Human Rights at Cambridge UniversitySharath Srinavasan is Director of the Centre of Governance and Human Rights at Cambridge University and a Fellow in Politics at King’s College, Cambridge. His research focuses on Africa’s international relations, the politics of international intervention (human rights, humanitarian, peace and security), political violence and armed conflict, and the politics of the Horn and East Africa, especially Sudan. He is also interested in the ideas and practice of democracy in the developing world, governance, new technologies and political activism. His speech explored China’s role in Africa.

Soft power – the use of co-option and attraction in place of coercion and payment – has a Chinese pedigree in the form of the seventh-century thinker Lao-Tzu. Following Joseph Nye, we could compare Machiavelli’s advice that it ‘it is much safer to be feared than loved’ with Lao-Tzu’s maxim, ‘A leader is best when people barely know he exists, not so good when people obey and acclaim him, worst when they despise him’. China is an emerging power, but for now it prefers to rise quietly and inconspicuously, pursuing foreign policy aims through soft power.

But soft power is a fuzzy concept: it is difficult to identify causes and effects; ‘hard’ power, too, is symbolic and soft – the deterrence and prestige afforded by nuclear weapons, for example; soft power requires concrete resources. Nye suggests ‘smart power’: the ability to combine attraction with hard coercion and payment. This requires ‘contextual intelligence’ and adaptability.

China places its involvement in Africa within a ‘south-south’ framework, stressing solidarity between developing countries based on respect for sovereignty and non-interference in the internal affairs of its partners. This stance is attractive to African leaders such as Zimbabwe’s Mugabe who have no appetite for lectures from Westerners. China has also sought to propagate its own past as one of peaceful exploration, cooperation and trade with Africa through the centuries – in contrast with Western imperialism.

Over the past 20 years in particular, trade, aid and investment have flowed between China and Africa in ever greater volumes. In 2000, bilateral trade volume for the first time exceeded US$10bn. By 2008 it had reached US$106.8bn. The number of African countries with which China has trade of more than US$1bn is now 20. Oil from Angola, Sudan, the DRC and Equatorial Guinea have been imported to fuel production in the ‘workshop of the world’. Aid has principally taken the form of development through construction of infrastructure: dams; railways; buildings; bridges; airports; telecoms.

More recently, however, China’s emergence as a major global player has placed a strain on its solidarity-based approach. With increased influence comes increased responsibility, including the responsibility to criticise the domestic affairs of other countries. China’s changing approach to the Darfur conflict over the period 2004–2008 is illustrative. Initially, China was reluctant to breach its principle of non-interference and jeopardise its considerable commercial interests in oil-rich Sudan. But by early 2007, China felt responsible enough, and conscious enough of its role as a major world power, to support a UN resolution to deploy UN peacekeepers in Darfur, albeit with a demand for Sudanese consent. And in early 2008 – the year of the Beijing Olympics – China’s desire to be seen as a responsible rising power resulted in attempts to informally persuade Khartoum to heed UN resolutions.

China stopped short of advocating compulsion or sanctions, but she no longer observed strict ‘non-interference’. In the past, the Chinese would have dismissed a humanitarian crisis such as Darfur as the domestic business of a sovereign country. Today, the combination of an increased – and thus threatened – economic stake with a rising sense of international presence has dragged China into active intervention.

H. E. Ambassador Pekka Huhtaniemi

Ambassador of Finland to the United KingdomIn June 2010 Pekka Huhtaniemi left his position as Under-Secretary of State at the Finnish Ministry for Foreign Affairs, which he had held since 2006, and began work as Finland’s ambassador to the United Kingdom. He has previously served as Ambassador to Norway, Finland’s Permanent Representative in Geneva, Special Adviser to the Prime Minister, and Minister Counsellor and Deputy Permanent Representative (economic and social affairs) at Finland’s Permanent Mission to the United Nations, New York. His speech considered the Finnish approach to hard and soft power.

Soft power is nothing new. During the Finno-Soviet War of Continuation, one of the many conflicts that made up WWII, Prime Minister Churchill tried to persuade Finland’s Marshall Mannerheim to withdraw his men from the Karelian front, an example of soft power as the art of persuasion. In this case, it failed. Mannerheim rejected Churchill’s plea, and Britain formally declared war on Finland. Churchill used the full arsenal of diplomacy, both its hard and its soft forms.

At her inauguration, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton said that the Obama Administration’s foreign policy would be based on three Ds – Defence, Diplomacy and Development. Finland is too small to exercise much power, whether hard or soft, though the emphasis is clearly on the latter. But Finland is able to exercise influence as part of a larger body – the European Union (EU). The EU exercises immense soft power, with its arsenal of variously calibrated relationships, from co-operation and free trade agreements to full membership. The process undertaken by national applicants to join the EU entails a long and comprehensive process of reform.

Finland does also exercise hard power. Since 1956, the country has been a major contributor to peacekeeping missions. Peace keeping and civilian military cooperation are examples of the positive potential of hard power, which can in turn enhance a country’s reputation and thus soft power. Whatever the form of power used, it must be anchored in international rules.

There may be a gendered aspect to international relations, and to the interplay of hard and soft power. The Ambassador argues that women often have a positive, pacifying effect in conflict zones, citing the example of Northern Ireland and Chechnya. He suggests that the Middle East is another zone of conflict that might benefit from a stronger female role in conflict resolution.

Finland’s relationship with Russia is healthy. Now that the purchasing power of Russians has increased, many of them are buying summer homes in eastern Finland. Face-to-face encounters between ordinary Finns and Russians can only have a positive effect on the countries’ diplomatic relations.

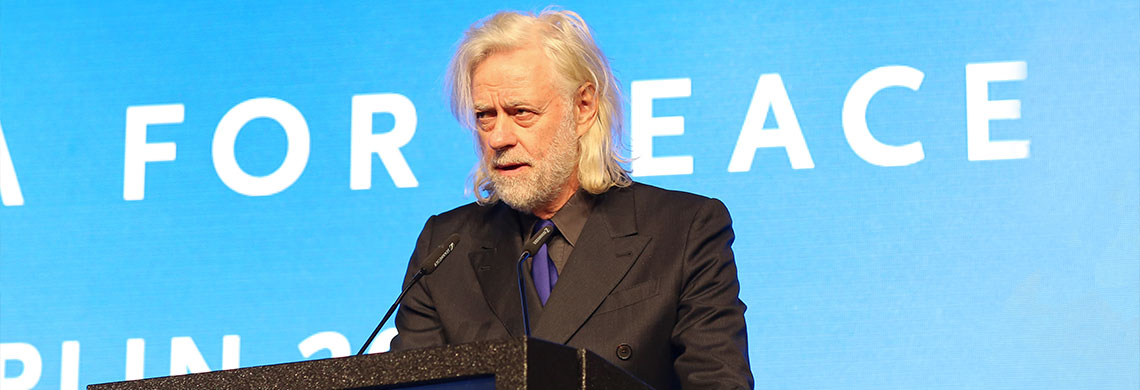

Martin Bell

UNICEF UK Ambassador for Humanitarian EmergenciesFormer British MP (Independent) and War Correspondent

Martin Bell is the UNICEF UK Ambassador for Humanitarian Emergencies, a position he assumed in 2001 following a distinguished career as a war correspondent for the BBC. His journalism spanned 90 countries and 11 wars and was recognised by the Royal Television Society's Reporter of the Year award in 1977 and 1993, and by appointment as an Officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE) in 1992. After leaving journalism, Bell wen on to become the first British independent MP since 1951. His speech considered the ‘CNN Effect’ in warfare and foreign policy.

Why do the Western powers exercise force in some countries and not others? Why do they then withdraw and what affects the timing? The impact of negative journalism – the ‘CNN Effect’ – often forces decisions. This is linked to the ‘civilianisation’ of warfare. In Bell’s view, the Geneva conventions on the treatment of civilians in warfare ‘might just as well not exist’, since war casualties today are about 90% civilian and only about 10% military.

International conflicts are increasingly interdependent. The September 2001 terrorist attacks in New York, for example, were arguably part of a chain of events stretching back to the Western powers’ recognition of Croatian independence and the subsequent war in Bosnia. Muslim victims in that war inspired jihadist fighters elsewhere in the Muslim world. The chain of events is not entirely causal, but one would not have happened without the other.

Hard power is seldom successful. For example, the Marsh Arabs were encouraged to rise up against Sadam Hussein, with disastrous results. And there is no military solution in Afghanistan, where we British seem to have forgotten our history: this is Britain’s fourth Afghan war, and it has parallels with the Second Anglo-Afghan War of 1878-1880. As the book The Utility of Force argues, one can lose by winning and win by losing.

Journalism should be a moral profession, for it affects the conduct of operations by influencing public perception and narrative. But since 9/11, journalism has suffered. A series of high profile abductions have made journalists too frightened to mix with the population they are meant to be covering. Embedded journalists, in turn, trade freedom for access.

Hard power is of little use with most of today’s challenges: nuclear weapons, jihadism, collapsed states, refugees, piracy, suicide bombers, ‘black swan’ events. These challenges can only be met by scaling back hard power, and focusing on soft power instead. The International Criminal Court in the Hague is one successful example of soft power, because it does affect the behaviour of international actors and thus outcomes in international relations.

Anna Fotyga

Former Foreign Minister of PolandAnna Fotyga is a Polish economist, politician, former Member of the European Parliament and former Minister of Foreign Affairs of Poland, in the successive cabinets of Kazimierz Marcinkiewicz and Jarosław Kaczyński. She is Poland's first woman to serve in the role. While in office, Fotyga’s foreign policy was based on the idea of a strong, independent Poland willing to confront Germany or Russia when necessary. She also pursued a policy of close alignment with the USA. Her speech was about Poland’s role in Central and Eastern Europe, both in 1989 and today.

Henry Kissinger suggests that ‘what is possible [for a state] depends on its resources, geographic position and determination, and on the resources, determination and domestic structure of other states.’ This is the definition of hard power Fotyga prefers.

The collapse of communism in Poland was the result of a peaceful revolution based on democratic ideals that swept through central Europe and Russia, liberating nations suppressed within the Soviet empire. The changes in Central and Eastern Europe were the result of a snowball effect. In order to secure the gains of the revolution, Poland must stand in solidarity with its neighbours in the former Soviet sphere, from the Baltic states in the north to Georgia in the south. Such support must also be concrete: Kissinger’s definition points to resources, including natural resources. Poland is currently exploring for shale gas, which would reduce the country’s dependence on Russia and allow it to assist its international partners.

Foreign policy must consist of a mix of hard and soft power, depending on the timing and circumstances. The latter is heavily advocated by President Obama, though in practice hard power still makes up a significant part of his foreign policy. A country’s foreign policy, and the balance it strikes between hard and soft power, should be determined by that country’s responsibilities, not concerns about perception or media image. Looking back at my time as Poland’s foreign minister, perhaps I could have used more soft power, but I do not regret the appropriate exercise of hard power.

Membership of the European Union has forced Poland and other countries, such as Germany, to adjust their attitudes over a very short period. Much of the history of Polish-German relations is tragic, but in today’s EU, the two countries have seen a confluence of interests. Perhaps this speaks to the transformative, soft power of EU expansion?

Philip Dodd

Visiting Professor at the University of the Arts LondonPhilip Dodd is a broadcaster, writer and curator who has won numerous awards in the fields of broadcasting, publishing and cultural entrepreneurship. He has curated major arts, film and architecture exhibitions at venues such as the Hayward Gallery, and from 1997 to 2004 he served as Director of the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London. In 2004 he left the ICA to found the agency Made in China, which develops cultural and educational projects between China and the UK. His speech compared American, Chinese and Indian soft power.

‘Soft vs. Hard Power’ is a false dichotomy. Both the CIA and abstract impressionism worked on behalf of the U.S. during the Cold War. And soft power often grows out of hard power. Post-independence India demonstrates the limits of soft power without hard power. China’s spectacular Beijing Olympics were an example of soft power as the continuation of hard power by other means.

There is no essential nature of soft power, but rather a ‘family resemblance’ between different examples of it. Compare New Labour's 'Cool Britannia' campaign to the enduring appeal of the Statue of Liberty or the Empire State Building, or to the Chinese model of economic modernisation, for example.

Soft power is easy to supply but useless without demand. American soft power is based on culture as a way of life. We should not overlook the importance of private enterprise in generating soft power – Hollywood and McDonalds for the United States, for example. The changeover form Bush to Obama has also had an effect. But in the wake of Afghanistan and Iraq, American soft power is waning. Chinese and Indian soft power, on the other hand, has great potential.

China’s soft power has centred on state-run initiatives: for example, government funding for the Confucius Institute, an English-language news channel. China is perhaps focusing on the wrong soft power: rather than state-run initiatives, they ought to focus on things that are already popular and vibrant globally such as Chinese medicine and contemporary Chinese art. China’s greatest strength in terms of soft power is that it offers an alternative, non-Western model of modernisation. This is especially potent in other Asian countries. China has a democratic deficit. This compromises its soft power in some theatres, but in others it facilitates cooperation with governments who do not wish to be lectured on democratic reform.

Both China and India need to make the shift from ‘Made in China/India’ to ‘Created in China/India’. China’s strength is its infrastructure. India’s strength is its credible democracy. Soft power is increasingly important for three reasons: there is a crisis of the political class; there is a shift to narratives in international relations at the level of the State and national politicians; new technologies facilitate networking.

Prof. Inderjeet Parmar

Head of Politics, Manchester University; Vice-Chair, UK International Studies AssociationProfessor Inderjeet Parmar heads the University of Manchester’s Politics Department where he lectures on US foreign policy and Anglo-American relations and researches the role of institutions such as Rockefeller, Carnegie, Ford and the German Marshall Fund of the US in shaping US foreign policy, promoting Americanism, and combating anti-Americanism abroad. His speech looked at hard and soft power in US foreign policy.

Soft power and hard power are intimately interlinked. In actual political practice they are bound up. One cannot understand soft power in isolation. Baden Powell described British rule in Africa in the 1880s as ‘an iron hand in a velvet glove’. More recently, General McCrystal argued that the US was ‘killing them softly’ in Afghanistan. The popular understanding of soft power is that it is very soft, cuddly and anything but warlike. Is it suspiciously left-wing? Joseph Nye’s formulation ‘smart power’ was a way of making soft power palatable to the US Congress. Hard power is tangible to politicians and voters.

At a domestic level, power has always consisted of both hard and soft elements – all governments need a social base. Legitimacy is not only built through coercive power, it is also based on authority. Attractive cultures do enjoy tangible foreign policy goods. Machiavelli argues that a prince who can portray a positive image enjoys real benefits. What soft power structures are there in the US? Public and cultural diplomacy; strategic communications; democracy promotion; US Aid and development strategies. These things are relatively minimal in Washington DC – look at the budget of the US Ministry of Defence. Britain and France spend more than the US on public diplomacy despite being so much smaller. In effect, the US is a hard power nation.

What might effective soft power exercises look like? Soft power programmes must be engaging, not propaganda. Programmes must be two-way, candid (admit that the country in question has deep-seated problems), honest, self-critical, and long-term. For example, in the 1950s Kissinger established a summer seminar in Harvard for European elites, including lectures, baseball games, concerts, and restaurants. The idea was to have them engage with American life, and thereby eliminate European neutrality in the Cold War and anti-Americanism in Europe. He did it for over twenty years. People are more effectively influenced through informality than formality.

Some bad examples of soft power? US information control policy in Iraq after the 2003 invasion. It was privatised. The companies knew nothing about the Middle East and had no experience of psychological warfare. They had some idea of creating a sort of Arabic Germany in the Middle East. They created TV channels that no-one watched. Sensing the crisis, the US military started bribing Iraqi journalists to write positive stories about the military. The LA Times discovered this and completely undermined it. You must show respect to the audience, tell the truth.

Soft power is not a theory or principle, it is practical and mixed with hard power. The notion that America is in decline plays an important role here: after two military crises and an economic crisis, soft power is making more and more sense. Much of the American administration has a very militaristic mindset. In confronting complex international issues, they prefer tangible military strategies. Many Americans believe that US power is benign, but many people in the world believe it is malign, or that America is an empire – in the Middle East, for example. International aid is a form of hard, not soft power. It creates dependency, and when it is withdrawn, the effects are felt keenly.

Janusz Onyszkiewicz

Former Defence Minister of PolandJanusz Onyszkiewicz is a Polish mathematician, alpinist and politician, and was a vice-president of the European Parliament's Foreign Affairs Committee from January 2007 until mid-2009. In the 1980s he was spokesman for the anti-communist Solidarity movement, and was arrested and interned after the introduction of martial law in Poland in December 1981. After the fall of communism in 1989, Onyszkiewicz became a member of the Polish Sejm. He was Minister of Defence twice, in the cabinets of Hanna Suchocka (1992-1993) and Jerzy Buzek (1997-2000). His speech considered the Solidarity movement as an example of soft power.

According to Francis Fukuyama’s The End of History and the Last Man, the modern, technologically sophisticated, market-based economy together with a socially mature democracy may be the end point of humanity's sociocultural evolution and the final form of human government. Not only do democracies have domestic benefits for their citizens, but a neighbourhood of democracies tends to be a safer, friendlier, more pleasant place to be. If we accept this, we might ask what means we should use to encourage and accelerate this transition? How should we spread democracy? With what instruments? In the case of Poland, communism was defeated by soft power.

It was previously thought that only a cataclysmic event, akin to WWIII, could achieve this, for such was required to defeat fascism. Jean-Francois Revel’s How Democracies Perish suggests the world can look forward to nuclear armaggeddon. And within Poland, there is a long tradition of physical resistance to assert independence. But in the twentieth century, the Warsaw Uprising (1944) and the Hungarian Revolution (1956) were so traumatically unsuccessful that there was no appetite for a repeat. In any case, the outcomes of violent revolutions are never predictable. Some small elite may seize control, making the situation even worse. As Rousseau wrote in The Social Contract, ‘How can a blind multitude, which often does not know what it wills, because it rarely knows what is good for it, carry out for itself so great and difficult an enterprise as a system of legislation?’ And as Dostoevsky’s Demons tells us, conspiracies, by their very nature, demoralise.

So how were we able to move forward in building a civil society? We first had to create an image of how we would like our country to look. The term ‘normalcy’ was used in reference to a Western European democratic standard. After the strike in Gdańsk, a new political situation was created. This was decisive, because the authorities decided to resolve the problem with negotiations rather than force. The new movement, under the umbrella of the Solidarity Union, had elements of soft power. There was no use of force, and there was much voluntary endorsement from elements such as the Catholic Church, which in Poland is a force to be reckoned with. The authorities eventually decided that the only way to save the communist system was through martial law. In a limited sense this was very effective, but it turned out to be a political flop. This exercise in hard power saw 10,000 people imprisoned, doing more harm than good to the authorities’ cause. This shows that hard power simply does not work under certain conditions.

Two high-profile UK politicians played key roles: Malcolm Rifkind, the Foreign Secretary, came to Poland and challenged the leaders to meet openly with Solidarity. Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher met with Lech Wałęsa, a nobody at the time, signalling that the West would not accept the freeze-out of Solidarity. This opened the way for negotiations. These symbolic gestures, examples of soft power, were truly effective.

What lessons can be drawn from the Solidarity process? There is cause for both optimism and pessimism. Firstly, Solidarity came at precisely the right moment: the soft power or attraction of communism and socialism were waning. It had run out of ideological steam. Secondly, in Poland there was a sense of belonging to a common Western culture. So much Polish culture has its roots in the West. There was a desire to come back into the fold. Poles find the idea of emulating Russia laughable. Finally, democracy can be broken with hard power, but building democracy requires soft power. It is crucial to have the moral argument on one’s side.

Teresa Patrício de Gouveia

Former Foreign Minister of PortugalTeresa Patrício de Gouveia, GCIH, is a Portuguese Politician and head of a number of Portuguese institutions. She has been a member of the European Council, Secretary of State for Culture (1985-1989), Secretary of State for the Environment (1991-1993), Minister for the Environment (1993-1995), Secretary of State for Portuguese Communities (2003-2004), and Minister of Foreign Affairs (2003-2004). In her speech, she suggested a new, ‘organic’ conception of international relations in the twenty-first century.

Perceptions matter more than facts in international relations. We act according to how we see the world, not how it actually is. This is important in an era of emerging powers, as we move to a multipolar world. Without international leadership, states tend to antagonise more often, as Niall Ferguson wrote in Colossus. Unfortunately, the U.S. seems to be surrendering its leadership in a problematic way.

The terrorist crisis of 2001 and the financial crisis of 2008 demonstrated two things: the preeminent power in a unipolar global order is not immune to attack. And the unregulated market model, which reigned triumphant in the post-Cold War world, is not fail-safe. Then the Beijing Olympics and the crisis in Georgia demonstrated that China and Russia could not be dismissed as major players. Couple this with the rise in international stature of Brazil and India, and it is clear that perceptions are changing. Today, the U.S. is not alone as an international power. And international challenges require international solutions.

How can a country like Portugal contribute to the construction of a new international relations architecture? This conventional wisdom is that such a small country cannot have an autonomous foreign policy. Portugal should be a constructive player, but also further its national interests within international organisations. If the U.S. is content to be less active on the international stage, any country should be prepared to take a role. September 11 changed the international order, for it changed the U.S. approach from reticence to the application of overwhelming power. But this latter strategy is at a dead end, and 2008 saw a further transition in U.S. foreign policy.

The experience of the last 20 years illustrates the twin dangers of excessively optimistic ('the end of history') and excessively pessimistic analyses. Striking a balance will be key in the years to come. It is not yet clear whether the U.S. is preparing to relinquish power to others, such as China, or simply refraining from exercising its still considerable strength. Even if we perceive a transition to a multipolar world, we may be mistaken. The relationship between perception and reality is reciprocal – each informs the other.

The Brazilian-Turkish initiative on Iran, which was even able to bring together China and Russia, indicates a new dynamic of third players. The initiative failed, which shows we still have some way to go. But at least we can see the destination.

Paul Berman's The Flight of the Intellectuals suggests that there are no more models, that ideology is dead. If this is true, perhaps biology could serve as an alternative heuristic tool. Many natural scientists are now trying to apply their own concepts and laws to social phenomena. Why not take inspiration from biology when analysing our current international order? I do not believe in a world government, but rather a multiplicity of ad hoc, issue-specific coalitions. I foresee an organic style of international relations. This is the only way to bring order and security to the international community.

Portugal should privilege relations with the Portuguese-speaking world, taking advantage of cultural affinity to enhance security in Africa and the South Atlantic. We must build up strategic relations with fast-growing, resource-rich, democratic emerging power Brazil. The same is true with regard to South Africa and Portuguese Africa. These countries are the future, Portugal has a stake thanks to shared language and history, and these countries in turn provide access to important partnerships, so we would be plugging into a larger network. To get the best out of this newly developing, organic world order, one needs to be a bit creative and inventive.

Jack McConnell

Former First Minister of ScotlandJack McConnell is a Scottish Labour politician who has been the Member of the Scottish Parliament for Motherwell and Wishaw since 1999, and served as the third First Minister of Scotland from 2001 to 2007. To date, he is the longest serving First Minister in the history of the Scottish Parliament. His speech focused on the challenges of peace keeping and international development.

The collapse of the Berlin Wall twenty years ago set off a wave of democratisation not only in Europe, but also in post-colonial Africa. The nature of international relations has changed. Simple border conflicts or clashes between large power blocs are increasingly rare. More and more, conflicts result from religious and ethnic divides, or power politics within a country. We need to not only deal with the conflicts themselves, but also the causes of these conflicts. And that makes reconstruction and development in a post-conflict context absolutely vital. Conflict prevention and the establishment of sustainable peace are by far the primary foreign policy challenges of the twenty-first century.

There is also the threat of fragile states: over one billion of the world's people live in fragile states. The number of weak states in the world far outweighs the number of strong, stable ones. Half of the world's poorest people live in unstable states. In this interconnected, globalised world, it is the responsibility of the more stable states – particularly those with a colonial history – to help strengthen the weaker members of the international community.

This aid must be an investment. At the moment, there are 18 peacekeeping missions under the auspices of the U.N., with a total 116,000 personnel. The total annual cost of those missions for 2008 was just over seven billion euros. This is unsustainable. In peacekeeping, the trend towards integrating civilian and military aspects needs to be accelerated. Prevention must also be improved. The role of mediation and early warning systems must be enhanced, natural resources must be managed in a transparent and equitable manner.

Around a third of conflict situations that are halted with a peace agreement slip back into conflict within five years. To improve this result, we need to focus on five key elements. First, we need to help create independent, well-trained, trusted justice and security services. Second, we need to put in place the foundations of a successful revenue, taxation and customs system. Third, we need to create jobs so that there is a real peace dividend discouraging people from entering back into conflict. Fourth, we need to promote elections, strong parliaments and the democratic process, as well as strong, elected local government. Fifth, and most vital of all, are improved public services, particularly education, but also health, clean water and other essentials.

H.E. Ambassador Birger Riis-Jørgensen

Ambassador of Denmark to the UKBirger Riis-Jørgensen is Denmark’s Ambassador to the United Kingdom. He joined the Danish Foreign Service in 1976 and was posted to the Danish Delegation to NATO in 1979 where he served as Denmark’s representative on the Political Committee and subsequently on NATO’s Defence Review Committee and Executive Working Group. In 1996 he was appointed Under-Secretary, responsible for Africa, Asia and Latin America and all Danish bilateral development assistance. In 2000 he was appointed State Secretary (Foreign Trade). His speech considered the Danish approach to hard and soft power.

What does the twenty-first century mean for Denmark? What instruments does Denmark use? What challenges does it face? How does Denmark look after its interests? Globalisation creates an international agenda. New international players are emerging in Africa, Asia and elsewhere. Denmark's interest lies in contributing to the fight against common challenges, such as terrorism, nuclear disarmament, climate change, sustainability and mass refugee flows.

The European Union is the most important focus of Danish foreign policy. Denmark is an export-oriented economy, and the EU represents a common market of 500 million Europeans. The EU has been one of the stabilising anchors of our time. Tariff competition is a thing of the past. The EU is founded on freedom, democracy and the rule of law, making it an ideal channel for Danish foreign policy. Its biggest achievement is the strong embrace of new member states within the European family. For that reason, it is important to encourage the Balkan countries and Turkey to attain the requirements of membership.

The EU helped Denmark weather the controversy resulting from depictions of Mohammed in the magazine Politiken. Certain interested parties in Muslim countries deliberately stirred up trouble. During the twentieth century, Denmark's key security threats were Germany and the Soviet Union. It was in our interest to see these relationships multilateralised. The EU is ideally suited to this end.

Denmark is a member of NATO, which was set up to protect individual states under an umbrella of united deterrence. But Article 5 offers deterrence for international terrorism. In Afghanistan, we need to see more progress in building a security machinery there, so as to demonstrate success to electorates at home, who tire quickly of war. For this reason, there is a soft power element of whether conflicts are seen as legitimate within democratic states. It is not simply a question of whether we have the technical capacity, or hard power, to sustain a conflict.

Altogether, more than 20,000 Danish soldiers have served in NATO missions, so hard power is a normal instrument of Danish foreign policy. But this hard power must be exercised within an international legal framework, which serves the interests of small countries like Denmark.

Cooperation between the Nordic countries is another means by which Denmark coordinates policy and protects its interests. Nordic cooperation, in such areas as reciprocal social benefits, is one of the finest examples of soft power. The concerted Nordic influence in the Baltic Sea has played a key role in the positive development of post-Soviet states there. The Arctic council addresses issues of the Arctic region on a multilateral basis.

The fundamentals of Danish foreign policy are cooperation with partners; strong rules; strong institutes such as the EU, NATO and the UN.

Andy Hull

Senior Research Fellow at the Institute for Public Policy ResearchAndy Hull has worked as a Senior Research Fellow at ippr since June 2008. Previously, he led the Secretariat for ippr’s independent, all-party Commission on National Security in the 21st Century. His areas of expertise include national and international security, terrorism and counter-terrorism, risk and resilience, defence, crime and policing, and community engagement. His speech surveyed the threats faced by Britain, and how they might best be tackled.

The challenges in international relations today are unprecedented in their diversity and complexity. With globalisation, there is an accelerated flow of goods, people and money, so power is moving from traditional actors to unregulated, diffuse global space. This is convenient for all types of criminal actors. There is a worldwide trend towards urbanisation. In addition, high unemployment on a global scale would prove destabilising, in the Middle East, for example. There has been a globalisation of conflicts. Ungoverned virtual space online is another ideal place for dangerous actors. Extreme weather events, such as the flooding in the UK in 2007, are becoming more frequent.

There is a serious terrorist threat, with at least 13 attempts in the UK since 9/11, and 30 ongoing operations, not only in London. The terrorists are homegrown in Britain. Many of them are of Pakistani ethnicity, complicating Britain's long history of bilateral relations with Pakistan. Britain has exported terrorists to other countries. For example, Richard Reid, the 'shoe bomber' in the U.S. Or Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, who beheaded Wall Street Journal correspondent Daniel Pearl.

So where in Britain headed? First, Britain's authorities need to develop a conceptual level of power, bringing on board a number of different actors. To do that, they first need to demonstrate that security policy is legitimate. Second, Britain is a middle-sized power in decline, so it needs to strengthen institutions such as NATO and the EU. Britain must be a constructive player in Europe, helping to forge the EU as a coherent unit. Third, British politico-civic culture must move from a 'need to know' culture to a 'responsibility to provide' culture.

Andrew Sparrow

Senior Political Correspondent, Guardian OnlineAndrew Sparrow is the Senior Political Correspondent for the Guardian Online, responsible for covering the latest developments in British politics. Sparrow has written primarily about British politics, covering key issues such as the MP's expense scandal and the ongoing controversy surrounding Britain's invasion of Iraq. His articles about Iraq followed the entire issue, from the early stages of the invasion to the Chilcot inquiry, during which time he maintained a live blog on the enquiry. His speech scrutinised some of the 'myths' surrounding Tony Blair's decision to take Britain to war.

The art of spin and government communications are arguably one aspect of soft power. The war in Iraq is now seen as a presentation disaster for Tony Blair's government, a collision of 'New Labour's obsession with spin, and George Bush's neo-imperialism'. For example, a majority of Britons believe Alastair Campbell lied. But there are a number of myths surrounding the Iraq war, and the so-called 'Dodgy Dossier' may actually have been a good thing.

Myth 1: That Blair had a choice between war and peace in Iraq. In fact, the UK faced the choice of supporting a war that would have happened anyway. Blair decided that a US invasion as part of a broader international coalition was better for world peace and stability than the US going it alone.

Myth 2: That Britain was merely America's lapdog. In fact, while oil may have played a role in American motives, the self-proclaimed liberal interventionist Blair did seem to believe that there was a moral argument for war.

Myth 3: That Blair took the UK to war without public support. In fact, the vocal opposition obscured polling figures, which showed that support for the war was at 53 per cent in March 2003, and 60 per cent in April 2003. It was only the following year that a stable majority of opponents to the war emerged.

So why was the Dodgy Dossier so bad? The government chose to use Iraqi weapons of mass destruction as the legal basis for going to war. To this end, there is evidence that it the Dossier was 'sexed up' for presentation purposes. But despite these issues, Blair's reasons for publishing the dossier were quite sound. He wanted to take the public with him, and thought that giving them access to the same information he had was the best approach. Indeed, New Labour had a record of 'government by dossier'. This was as much a part of their freedom of information agenda – policy decisions should be justified and transparent – as it was an exercise in spin.

Hard power does matter. It isn't the journalist who guarantees free speech, but the soldier. But if hard power fails, so will soft power. In Iraq, the real issue was the disastrous course and outcome of the war, not the questionable arguments. Had the invasion and occupation been a success, the war would probably be much more popular today. Soft power elements such as spin are actually dependent on hard power outcomes. Many of the arguments against the war in Iraq are retrospective – for example, that planning was inadequate – and based on results rather than original premises.

Dr. Andrew Dorman

Senior Lecturer at King's College London, Associate Fellow at Chatham HouseAndrew Dorman is a Senior Lecturer and an Associate Fellow at the Royal Institute of International Affairs, Chatham House. His research focuses on nuclear strategy, civil-military relations, decision-making and the utility of force utilising the case studies of British defence and security policy and European Security. He has held grants with the ESRC, British Academy, Leverhulme Trust, Ministry of Defence and US Army War College. His speech was about Britain's role in the world.

The United Kingdom has three foreign policy priorities: North America, Europe, and the Commonwealth. The balance between these three priorities has shifted over time. Dean Acheson, former US Secretary of State, famously said that 'Britain has lost an Empire, but has not yet found a role'. Britain has no vision of where it is going as a 'post-middle-sized-power'. Britain's historical legacy is one of busy body interventionists. An imperial mindset remains.

Britain is also a trading nation, and heavily dependent as such, especially now that it faces a massive debt problem. There is little money available for projects such as international aid. Britain's population is ageing and growing, and British values are changing as the country becomes more globalised. There is a loss of confidence. Britain feels the need to justify its role on the world stage. For the French, in comparison, a global role is self-evident.

There are tensions in the 'special relationship'. The financial crisis turned on a New York-London axis. The centrality of these two cities in what became a global crisis is symptomatic of their enduring dominance, but there are problems in this relationship, too.

Leadership of the Commonwealth is one way Britain justifies its own position, on the U.N. Security Council, for example. For 70 years, Britain has successfully avoided making a decision on its future role. Does it still have the resources to decide in favour of active leadership? Britain is at the crossroads. The deliberately apolitical Queen Elizabeth II is exactly what Britain has needed to sustain the key institution of the Commonwealth. But what will happen when she is gone? This asset may disappear. The Queen herself is a form of British soft power.

Hubertus Hoffmann

President and Founder of the World Security NetworkDr. Hubertus Hoffmann is a German entrepreneur and geostrategist based in London, and a lawyer with a PhD in Political Science. He is President and Founder of the New York-based World Security Network Foundation, an international, independent, nonprofit organization, and the largest global elite network for foreign and security policy. After working for the nightly news at ZDF, Europe's largest television station from 1988 to 1990, Hoffmann became CEO of the radio business of the Georg von Holtzbrink publishing group, and later Managing Director for New Media in the Burda Publishing Group in Munich, building up 15 companies for new media in Europe from 1993 to 1995. His speech suggested improvements to the West's strategy in Afghanistan.

Which priorities, double strategies, moves do we need in our globalised world to promote security? One might take the craftsman and his tools as a metaphor, but the problem is that there is no single, correct tool for each problem. Different craftsmen, such as NATO or the EU, approach the same problem with different solutions. This is chaos. Finally, action comes too late. President Obama took half a year to come up with a half-baked solution on Afghanistan. Actions are uncoordinated, and G8 meetings, for example, are little more than show. In the business world, one needs concrete results within a specific time frame. In foreign policy, there is endless planning. A better approach would be based on a few rules:

Rule 1: Clarify the options. A crucial foundation of foreign policy is to analyse all the options. We need open discussion, opinion papers, policy papers, with nothing ruled out at first. General McCrystal's 10+9-year plan for Afghanistan was absurdly long.

Rule 2: Keep an eye on the bottom line. Businesses struggle to keep costs down, but there is no fiscal discipline when strategising for Afghanistan. We need cost effectiveness.

Rule 3: Think and act local. Hold fewer international summits, and focus instead on asking the local population what it needs, wants and thinks. For example, The Economist reveals that one in three Afghans hold a positive view of the Taliban, but only one in four think similarly about the central government. Perhaps a dose of federalism would help here?

Rule 4: We need double-strategies. We must take into account the wishes of the local population, other factors, costs etc. Once this has been established, we can choose the most efficient, cost-effective strategy and develop an action policy paper. After six months of dithering, President Obama could not even produce this! And no one bothers to ask what the people in Kandahar want. We always need a smart mix of hard and soft elements. We need to learn that soft need not mean weak, and hard need not mean strong. The reverse can be true.

Rule 5: We need a timeline. We must track outcomes against a set period, just like in business.

Rule 6: Foreign policy must be transparent. There should be reports and open debate about foreign policy priorities. Open, democratic societies must publicise rather than hide government aims. Governments should produce an annual report detailing the thinking, priorities and progress in foreign policy. There has been a shift in power from the legislative to the executive. Too often, governments hold secret discussions based on policy papers and then force their decisions through parliament. This must change.

Rule 8: We must be creative. Businesses are skilled at marketing products such as Coca Cola, but how can we promote our Western values. Our democracies have both flaws and virtues, but we should exploit our boundless creativity and emotive power and direct it towards geopolitical hotspots. As Einstein said, 'Imagination is more important than knowledge'.

We also need to take into account Afghanistan's neighbours. With regard to Iran, talk focuses on sanctions and military actions, but we should be supporting the opposition Green Movement with hundreds of millions of dollars. We could also undermine the moral authority of Iranian leaders by pointing to funds stored in Swiss bank accounts, for example.

Homeland security is currently intelligence-dominated. We first need to make clear that Al Qaeda are not Islamists, but merely petty criminals who offend Islam and insult the prophet. We need a global elite to promote codes of tolerance and respect worldwide. As Kant told us: peace is not natural, it must be organised.

Simon Berry

Head of the Third Sector Team, Defra; Founder and Director of ColaLifeSimon Berry is Head of the Third Sector Team at the Department for Environmental, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) and Founder and Director of ColaLife, an initiative that aims to use Coca-Cola’s distribution channels to deliver essential medicines to communities in need. He began his career by working with ODA, now DfiD, as a Technical Cooperation Officer from 1978 -1989. He had the initial idea for the ColaLife ‘pod’ in 1988 whilst working in Zambia on climate change initiatives. The idea only became a reality in 2008, however, when Berry posted a blog about his idea on Radio 4’s iPM website – the blog was picked up by Radio 4 and eventually came to the attention of Coca-Cola, who are now in the process of developing the first ColaLife pods. His speech reflected on what the emergence of a project like ColaLife means for international relations today.

Soft power is not only exercised by nation-states. Individuals and initiatives can also have soft power. The following definition of soft power is most relevant to my work: soft power is the ability to get what you want using attraction. I have no hard power, no staff, no project funding and no premises. But I have slowly gained support and notice thanks to the soft power of the ColaLife project.

ColaLife was developed in response to a number of facts and new developments. Fact 1: you can get a can of Coca-Cola pretty much anywhere in the world. Fact 2: An average of one in five children in developing countries die before their fifth birthday. Most of them from dehydration caused by diarrhoea, which kills more than AIDS, malaria and measles put together. Fact 3: This figure has not changed in 25 years. There has been no progress, so the current efforts to solve the problem aren't working.

Rural health centres in developing countries run on about 30% of the basic health supplies they need. But down the street is a legal, affordable, well-stocked retail market, with prices comparable to urban centres. How does Coca-Cola get to these remote areas? The crates make their way from the bottling factory by way of mule, motorcycle, cart, or whatever else is necessary, to far-flung consumers. These crates have empty spaces. This is where ColaLife comes in. We want to use this space not just to improve the life chances of children in developing countries, but also the image of Coca-Cola.

In April 2009, a radio interview caught the attention of Coca-Cola. So where does the power ColaLife has come from? First, the new convening power of the internet is available to both individuals and organisations such as ColaLife. Second, the consumer power to leverage corporate power allows us to harness ethical consumerism. The former gives you clout and gets you noticed – we caught the attention of the head of Coca-Cola's global stakeholder relations team. It also improved the concept. Instead of trying to persuade Coca-Cola to give up a bottle's worth of space in each crate, we worked out a way of utilising unused space. It also increased our confidence and credibility, as the idea was repeatedly challenged and honed.

What's in it for Coca-Cola? Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) has become an important competitive advantage to companies. As Andrew Wilson, Director of the UK's Ashridge Centre for Business and Society notes, 'shopping is more important than voting'. ColaLife is about harnessing consumer choices to create social goods. So why don't Coca-Cola just do it? Acting alone, they would have no credibility in the public health sector. They need 'the right partners' and a 'trusted third party' to help them and give the initiative credibility. The project is still in the preparation stages, but it is an illustrative example of soft power below the level of nation-states.

Prof. Dr. Jeffrey Haynes

Director of the Centre for the Study of Religion, Conflict and Cooperation, London Metropolitan UniversityProf. Dr. Jeffrey Haynes is the research and postgraduate studies associate head of department and director of the Centre for the Study of Religion, Conflict and Cooperation at London Metropolitan University and vice-chair of the International Political Science Association’s Research Centre, ‘Religion and Politics’. Prof. Dr. Haynes is recognised as an international authority in the fields of religion and international relations, religion and politics, democracy and democratisation, development, and comparative politics and globalisation. His speech was on the role of religion in international relations.

Stalin famously dismissed Catholicism as a political force by asking, 'How many divisions does the Pope have?' Religion may be (a) linked to state power (such as President Bush's Christian's influence) or (b) independent of sate power (such as the Anglican Church, or the Jewish lobby in the United States).

If we stretch Joseph Nye's idea of soft power to encompass non-state actors, we could well include religious groups and churches. Religion is not a value-free component of foreign policy. It reflects assumptions, values and beliefs, and can take the form of hard or soft power. For example, the aim of the Religious Freedom Act passed in the U.S. by President Clinton in the 1990s was to prompt Muslim states to open up to Christian missionary influence.

In the pre-Westphalian international order, borders were based on religious spheres of influence. Kingdoms had religious identities, and in the absence of citizenship or nationality, identity was religious in nature. The Treaty of Westphalia was the outcome of about a century of religious conflict.

Religious soft power amounts to values and ideas, and even an organisation like Al Qaeda relies on hearts and minds. Hard power in the form of terrorism is depleting that soft power influence. Cowing is not the same as convincing.

Regardless of their objectives, transnational religious forces seek to establish and cultivate cross-border actors. They seek to do this through the application and development of 'religious soft power'. This can be threatening to nation-states, since many countries are home to a variety of religious groups whose identity is more religious than national in nature: India's Hindus, Buddhists and Muslims, for example. Transnational religious actors, such as the Roman Catholic Church and Al Qaeda, have sought to apply soft power to the cause of religious and political change, in these cases in Poland and Saudi Arabia.

Concluding comments

As Srinavasan pointed out, soft power is nothing new: it can be identified in classical Chinese thought, for example. It is also difficult to distinguish between soft and hard power when instances of the latter, such as nuclear weapons, can produce soft power.With the exception of Bell, perhaps the most obvious point of consensus was the pointlessness of opting for either hard or soft power. They are not mutually exclusive strategies; rather, different conditions lend themselves to different approaches. This point was made most clearly in the accounts of Danish and Finnish foreign policy given by those countries' ambassadors (Riis-Jørgensen and Huhtaniemi). Soft power may be seen as 'suspiciously left-wing' (Parmar), but it can equally be seen as a byproduct of, and dependent on, hard power (Dodd). Many speeches amounted to apologies for soft power in quite specific contexts (e.g. Onyszkiewicz, Hull) without ruling out hard power in others. Hard power was most often seen as necessary in peacekeeping work (e.g. McConnell).

A further area of agreement was the sheer heterogeneity of 'soft power', with everything from Queen Elizabeth II (Dorman) through Japanese electronics (Anholt) to Al Qaeda (Haynes) fitting the bill. Nye proffers 'attractiveness, values, culture' and 'getting others to want to do what you want them to do' as loose definitions. Anholt's and Dorman's speeches most explicitly dealt with the former, while Parmar considered US soft power as an example of the latter. Both of these definitions of soft power are state-centric; that is, they imply the deliberate exercise of soft power by a given nation-state or government. Berry's discussion of the soft power enjoyed by an third sector initiative is an illustrative counter-example. And as Jones made clear, soft power, and particularly culture as soft power, is often something over which governments have little control, but with which they must reckon.

Indeed, even when soft power is used purposefully by states, this may backfire. There is surely some potential tension between using foreign and domestic policy to manage international reputations (Anholt), and pursuing a 'responsible' foreign policy, without regard to media image or perceptions (Fotyga). Anholt would perhaps argue that, over the long-term, a 'responsible' foreign policy is its own best PR. But if we are to believe Sparrow, outcomes matter much more than intentions in international relations and popular opinion. It would appear that last century's debates over means, ends and justification are very much still with us. Even such apparently innocuous aims as transparency can have both positive and negative soft power effects: compare Hull's argument that UK anti-terrorist policy must be seen as legitimate, with the disastrous results of what Sparrow called New Labour's 'government by dossier'.

The importance of perception in international relations was a recurring theme. Bell spoke of the 'CNN Effect' on foreign policy planning. Perception may have soft power implications, as in the Polish desire for 'normalcy' measured against a Western benchmark (Onyszkiewicz), or the more recent earthquake in perceptions regarding such Western paradigms as unregulated markets and American invulnerability (de Gouveia). But as the latter points out, instances of hard power – the Russo-Georgian conflict of 2008, for example – also affect perception.

Two speakers spoke of the need to harness the creative forces of capitalism to further quite different international goals. One argues that democratic values should be marketed in Afghanistan as effectively as Coca-Cola advertises its products (Hoffmann – though Anholt might disagree), while the other is planning to use Coca-Cola's supply chains to distribute much-needed medicines in developing countries (Berry).

The overwhelming majority of speakers treated soft power as unproblematically effective. In contrast, Jones and Bell showed how soft power, in the form of inconvenient images or cultural products, can undermine government aims. This ties in with Nye's point that images that may be attractive in some contexts – liberated, scantily clad Western women, for example – may be repellent in others. Srinavasan explored China's relationship with Africa to show how soft power may prove to be a double-edged sword: the need for recognition as a responsible, and increasingly powerful, member of the global community has undermined China's traditional policy of south-south solidarity and non-interference.