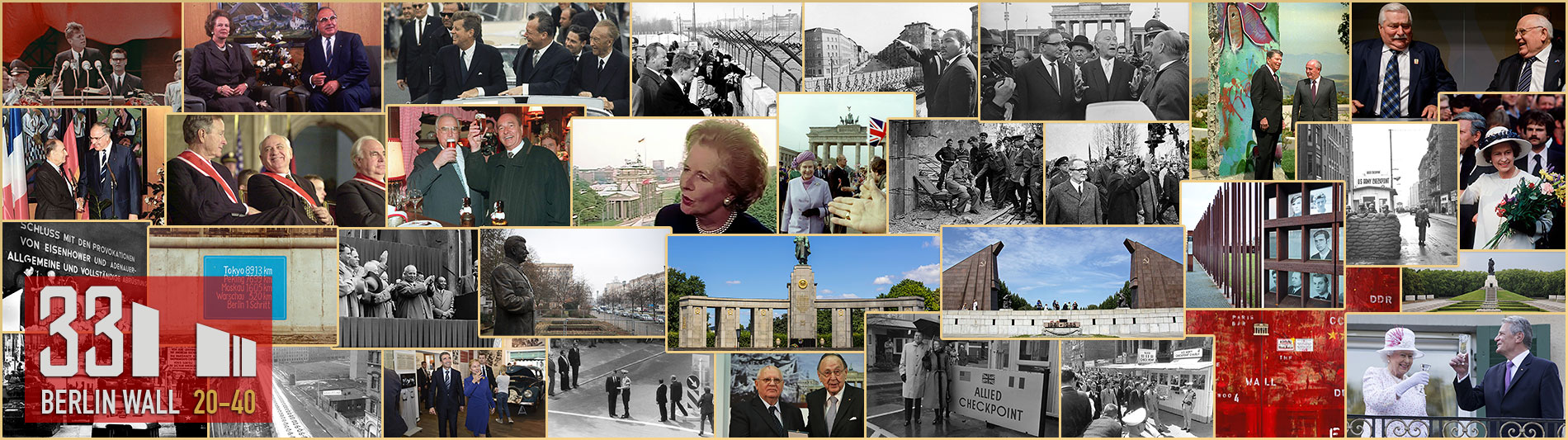

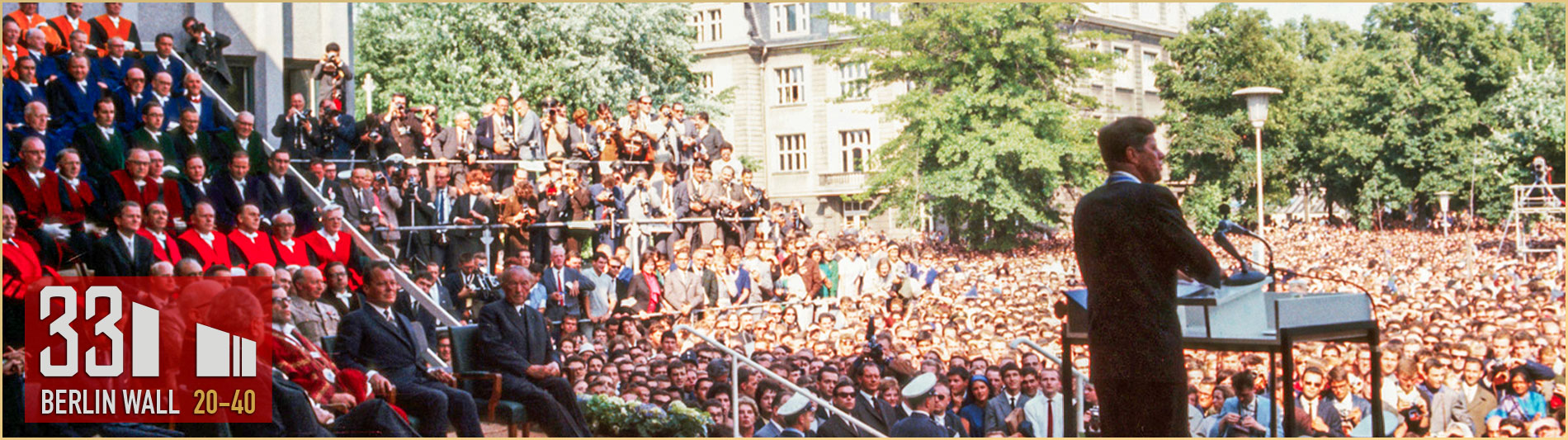

Berlin Wall 30 - From the Divided to the City of Freedom

The 30th Anniversary of the Fall of the Wall

Berlin; November 6th - 10th, 2019

The Berlin Wall 1961 – 1989

The Berlin Wall enclosed West Berlin from August 13, 1961 to November 9, 1989, cutting a line through the entire city center. It was supposed to prevent East Berliners and citizens of East Germany from fleeing to the West, but the Wall was unable to entirely stop the mass of people from fleeing. Consequently, in 1961, the SED, the ruling Communist Party in East Germany, began adding more border fortifications to the Wall, creating a broad, many-layered system of barriers. In the West people referred to the border strip as the “death strip” because so many people were killed there while trying to flee. With the downfall of East Germany in 1989, the Berlin Wall that the SED had for so long tried to use to maintain its power, also fell.

Construction of the Wall in August 1961

After the war, with the help of the Soviet occupying forces, the SED, the ruling Communist Party, began establishing a dictatorship in East Germany (GDR). Large parts of the East German population, however, did not agree with the new political and economic system. Consequently, a mass migration to the West began in the late forties, motivated by a mix of political, economic and personal reasons. By August 1961, East Germany had lost a sixth of its population.

The SED had begun sealing off the East German border to West Germany as early as 1952. Hence it became increasingly dangerous to flee directly to the West. Many chose to take advantage of the last loophole, and reached West Germany by crossing the sector borders to West Berlin, which were still open.

On August 13, 1961, the SED began erecting barbed wire to seal off the border all around West Berlin. Walls were erected within a few days. It was hoped that this would end the growing mass migration to the West once and for all. The SED also wanted to stabilize its power over the people in East Germany and to demonstrate its sovereignty to the world. But the barbed wire and walls were unable to completely stop escape attempts. Hence the border barriers in Berlin were continually expanded and reinforced.

Expanding the Wall, 1961 To 1989

Even after the Wall was built, the SED leadership was not able to completely stop the westward migration. On the contrary, because the Wall separated friends and relatives in Berlin, the pressure on East Berliners and people living on the outskirts of Berlin to flee became even greater. As people kept trying to flee across the border barriers, the SED kept expanding the border fortifications. What began as a single simple wall evolved into a complex, multi-layered border installation designed to prevent escapes.

At first, after every successful escape, border soldiers and pioneer units added temporary, individual barriers behind the border wall. After a border area had been established behind the Wall in East Berlin by 1963, large expanses of this area were also blocked off by a fence. In the mid-sixties the SED tore down buildings to make room for a uniform border strip that would provide border soldiers with an “unobstructed view and clear field of fire.” Over the following years more and more barriers were installed within this “death strip.” In the seventies a second “inner wall” (Hinterlandmauer) was added, blocking off the border strip to East Berlin and the GDR.

The Border Fortifications in the Eighties

The border fortifications were constantly being developed and improved. In the early eighties, the inner wall that closed off the border strip on the East German side was the first obstacle that fugitives encountered. Then they had to climb over a signal fence that when touched activated an alarm in the observation towers where the border soldiers were stationed. A carpet of steel spikes often lay at the foot of the fence with the sharp ends pointing upward, either to injure or deter fugitives. Officially they were referred to as “surface obstacles,” but the border guards called them “asparagus bed.” In the West they were sometimes called “Stalin’s lawn.” After a fugitive had crossed the patrol road and security strip, he had to get passed the “tank traps” that were designed to prevent an escape with a car or truck. In the inner-city area they were usually made of railroad tracks welded together and enveloped in barbed wire, thus also posing an obstacle to people escaping on foot. On the outer ring border a ditch was also added. The nearly 12-foot-high border wall was the last obstacle that a fugitive had to get over before reaching the West.

At some areas dog runs were also installed so that watchdogs could block the path, alert border soldiers of an approaching fugitive and deter him from continuing his flight.

At night the border strip was lit up brightly by a line of lamps allowing border soldiers to see fugitives in the dark. Both walls enclosing the border strip were painted white on the inner side so that a fleeing person could be easily recognized.

Watchtowers, occupied by border soldiers, stood approximately 250 meters apart. They were positioned so that the guards posted there could easily oversee the border area between two towers. Guards stood on the towers, monitoring the border strip and rear border territory, and ready to recognize fugitives in time to prevent their escape. The border soldiers were also expected to maintain surveillance on the area of West Berlin that bordered the Wall.

In the late seventies, the SED leadership had the border wall rebuilt. Hoping to achieve international recognition, the SED no longer wanted the East German capital’s public image dominated by the menacing border fortifications with their metal gratings, bunkers and vehicle obstacles. These types of barriers were removed from the border strip by 1983. This was possible because the new Wall had a much stronger “blocking capacity” and surveillance of all of East Germany and the rear border area was strongly improved. Hence the border fortifications became less crucial to preventing escapes.

By the late eighties, shortly before the Wall fell in 1989, most of the menacing obstacles between East and West Berlin had been removed from the Wall.

The Fall of the Berlin Wall

At the CSCE conference in Helsinki in 1975, the East German leadership agreed in principle, albeit without wanting to admit it, to the right of people’s to move freely and the freedom to travel. Afterwards, more and more East German citizens submitted applications to immigrate permanently to West Germany. An opposition movement had also developed in East Germany in the 1980s that expressed increasingly fundamental criticism of the political and social conditions. Environmental damage and economic stagnation also angered the general public, leading it to turn away from the East German state. Similar developments occurred in other Eastern Bloc states, for example in Poland, where the independent trade union Solidarnosc was established and struggled to achieve national recognition in November 1980.

After Mikhail Gorbachev became General Secretary of the Communist Party in the Soviet Union in 1985, the political situation in the Eastern Bloc slowly began to change. Gorbachev first tried to solve the serious economic and social problems using internal political reforms. In 1988 he gave up the Brezhnev Doctrine, a political principle central to Soviet foreign policy that demanded limited sovereignty of the Warsaw Pact nations. This change allowed the Eastern Bloc states to determine their own national policies. Hungary’s shift towards the West led it to demonstratively dismantle its border fence on May 2, 1989. The first hole was made to the “Iron Curtain.”

The SED was not interested in adopting the reform course of the Soviet Union for East Germany. But the widespread protest movement that emerged within the East German population at the end of the eighties and the growing migration of East Germans to the West brought the dictatorship to an end in 1989. The SED first found itself compelled to make concessions, for example to allow its citizens to travel. When a new emigration law was falsely announced on November 9, 1989, crowds rushed to the border and the Wall fell under the onslaught of people. The fall of the Wall led to the ultimate collapse of the East German state.